Article

A relocation Indian, also known as an urban Indian, is a Native American whose family was encouraged to leave its reservation during the 1950s. Initally focusing on the Navajo and Hopi tribes, the idea was introduced in the late 1940s as an effort to reduce the U.S. government's obligation to subsidize living conditions on reservations by assimilating Native Americans into mainstream U.S. culture. By the mid-1950s, the program was extended to all Native Americans. A large number of Native Americans volunteered and were enlisted to fight in World War II, while others left their reservations to work in factories producing goods for the war. At the end of the war, large numbers of Native American veterans chose not to return to their reservations, due to feeling uncomfortable on the reservation, yet many of them were no more comfortable in the outside world. Additionally, others who had worked in factories during the war never returned to the reservation, where wage labor jobs were hard to find. Ultimately, over 30,000 Native Americans relocated as a result of the Indian Relocation Act, which was officially passed in 1956.

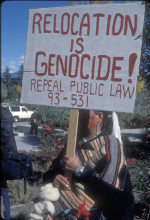

The Indian Relocation Act of 1956 has been critiqued as a continuation of the Indian termination policy first enacted by the U.S. government during the 19th century. In the case of the Indian Relocation Act, however, termination was executed as an expression of cultural genocide rather than mass murder. In the generations that have followed the initial urban migration of Native Americans, rates of poverty, substance abuse, and cultural assimilation due to racial and class discrimination have continued to increase in urban Indian populations. In essence, the Indian Relocation Act resulted in the isolation of relocation Indians from their communities and cultural practices.

The policy was terminated in 1962 after an outcry by Native Americans and special interest groups, who argued that the act in effect stripped Native American groups of their tribal sovereignties, with a resulting degradation of Native American lifeways as a result of increased poverty, disease, and unemployment, despite the earlier promises made by the act toward Native Americans. The effects of the act, however, persist.

"Dine woman holding protest sign," photograph by Lisa Law. (mss857-0011). Center for Southwest Research, University of New Mexico. All Rights Reserved. Use with permission only.

Manuscripts

References

Department of the Interior

1960 Emmons Cites Evidence of Indian Success in Relocation.

http://www.bia.gov/cs/groups/public/documents/text/idc016759.pdf, accessed

February 19, 2015.

Fixico, Donald Lee

1991 Urban Indians. New York: Chelsea House.

Murrin, John M., Paul E. Johnson, James M. McPherson, Alice Fahs, and Gary Gerstle

2008 Liberty, Equality, Power Since 1863, Concise. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Pub Co.