by Emily Cammack, Senior Hillerman Digital Fellow

Originally posted on Celebrating New Mexico Statehood, [date]

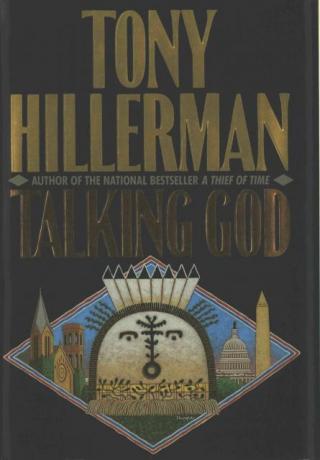

The dust jacket of the first edition of Hillerman’s 1989 novel TALKING GOD positions a depiction of a Navajo Yeibichai mask at the center of a representation of a Navajo sand painting. Designed by long-time Hillerman collaborator Peter Thorpe, the jacket design depicts the mask as flanked on either side by iconic emblems of the national government that was responsible for the effective genocide of millions of Native Americans as well as the forced removal of the Navajo from their homeland in the Long Walk of 1864. Framed between the Gothic facade of the Smithsonian and a paired grouping of the Egyptian obelisk that is the Washington Monument and the neoclassical dome of the Capitol Building, the novel’s cover, as well as its plot line, functions either as the epitome of continued cultural appropriation or as a nexus of multicultural creativity, collaboration, and intervention. In the novel, Navajo policemen Joe Leaphorn and Jim Chee, with the assistance of the gone-Native blond indigenous activist Henry Highhawk, de-escalate an international terrorist attempt in the nation’s capitol. Although it would make sense for the two Navajo cops to empathize with the Chilean underground radicals-cum-terrorists, tortured survivors of a U.S.-backed military coup whose people share with the Navajo a history of European colonization, settlement, and continued neoliberal deprivations, because the Chileans use Highhawk to gain access to the Smithsonian during a high-profile public event, the characters of Leaphorn and Chee are deployed instead on the side of “law and order.” In the process, a replication of a yei Talking God mask, showcased at the center of the novel's dust jacket, is used to elucidate the burgeoning debate and cultural activism concerning indigenous artifact repatriation, as well as doubling as an incendiary device, thus blurring the line between right and wrong, law and criminality, natural chaos and civilized disorder.

But cultural appropriation, collaboration, and intervention in Hillerman’s novels do not end with the 1989 cover illustration of TALKING GOD. The 1990 German edition of TALKING GOD, DIE SPRECHENDE MASKE, is illustrated with a wooden mask that can loosely be attributed to indigenous traditions from the U.S. Pacific Northwest. In this case, a German fascination with all things Native American creates a blanket synecdochic acceptance: any indigenous artifact will do to evoke Native American culture broadly conceived. But I find the use of this mask especially provocative, in that Germany has its own legacy of cultural appropriation. As Europe transitioned into late modernism, Expressionism as a literary and visual movement rose to the fore in early twentieth-century Europe. Grappling with the effects of accelerating industrialization and urbanization, and the associated effects of spatial and psychological displacement, fragmentation, and increasing isolation, the German Expressionists embraced the idea that art should express individual subjective experience rather than external objective observation. The use of color and the kinetic revelations of gestural brushwork in painting revolutionized how art was created and perceived. Subject matter, too, continued to evolve, and similar to the French post-impressionists from an earlier decade, German Expressionists found themselves fascinated with the detritus of Europe’s colonial legacies. Artifacts, especially masks, from Africa, Asia , and the Americas were pulled out of curiosity cabinets and museum archives to become the topical and psychological touchstones for many European painters, the most familiar painting of which may be Pablo Picasso’s DEMOISELLES D'AVIGNON (1907). German Expressionist artist Emil Nolde was another artist whose existential angst manifested in his artwork, and his 1911 painting STILL LIFE WITH MASKS bears an interesting and fraught comparison with the 1990 German jacket design for Hillerman’s TALKING GOD, whose plot line and imbricated polyphony of cultural appropriation and deployment is mentioned above. The leering faces, the distorted and exaggerated physiognomies, and the lurid colors of Nolde’s piece evoke the German book cover illustrated by Jurgen Reichert, and the effect on the viewer is one of almost fascinated revulsion. We want to look, but there is something uncanny and unnerving in the masks’ bared teeth, open mouths, and empty eyes. We shift our eyes but then attempt to return the gaze of “the talking mask,” the mask that speaks, but to whom, to what end, and to what revelation? In many ways, encoding “mysterious” communications, whether they pertain to psychological angst or criminal intent, behind the “mask” of cultural appropriation is a Western colonial endeavor that has persisted since the sixteenth century. Yet I return to the idea that Hillerman meant to operate as an ambassador rather than an exploiter, one who intended to introduce, educate, and intervene rather than appropriate, commodify, or demean indigenous cultures.