by Darcy Brazen, Digital Hillerman Fellow

Originally published on Celebrating New Mexico Statehood, 8/19/2016

As a Master’s candidate in American Studies at the University of New Mexico, working with Hillerman’s manuscript of The Ghostway sparked insights and vital connections with my own research in critical indigenous studies. A close reading that emphasizes historical events as they relate to contemporary struggles within Native American communities may enhance our understanding of the real and metaphorical ghosts that haunt our national consciousness.

Like Shakespeare’s Richard the III, Leslie Marmon Silko’s Almanac of the Dead, and Toni Morrison’s Beloved, Hillerman’s The Ghostway is perfectly suited to the moribund depths of deep introspection. Below the surface of a page-turning detective novel, the book is rife with chilling activity representing centuries of historical trauma. There is an overt demand upon the reader to suspend disbelief and recognize the influence of the supernatural, the unseen, and the spectral not only as mystery craft-work, but as themes that cross over to the social terrain of historical injustice. The reader must reckon with the burden of unresolved conflicts for the protagonist, Jim Chee, in a work of fiction peppered with haunted landscapes, ghosts, ghost sickness and uninhabitable chindi hogans. Chee’s angst is magnified by the loneliness of long highway drives, and the wild, high-desert mesas of his sleuth wanderings.

Are the ghosts that haunt Jim Chee just a narrative device spinning elements of suspense and fear? Certainly these fright-inducing literary mechanisms compose the standard fare of both western and mystery genres, but within The Ghostway the character of the Navajo police officer emerges as intimately linked to the world of ghosts, as he is also a holder of Diné cosmology and spiritual knowledge. What is the implication of considering haunting apparitions as more than a literary device, and of contextualizing Chee’s ghost sickness within an archive of historical phantoms?

It is interesting to consider the opportunity Hillerman presents us with to contemplate the ghosts inhered not just in the Navajo but white bodies as well, especially if we approach novels, at least on some level, as creative expressions that reveal the hidden, sometimes haunted consciousness of the writer and his times. As a methodology in writing, ghosting accounts for the lost and wrecked, the unseen but palpable reverberations of social chaos and death at the storied spectacular sites of our national imaginings.

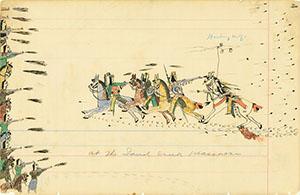

For example, Hillerman writes about Sand Creek, where the U.S. cavalry massacred Cheyenne people in 1864, even as Black Kettle waved a white flag in one hand and U.S. flag in the other. The Cheyenne carried out low-level hostilities on settlers moving into their unceded territory for years, and fought with the Lakota at Little Big Horn to defeat Custer’s unit in 1876.

Another significant, painful event Hillerman brings up is the famous battle at Wounded Knee. In 1890 where the Indian agent at Pine Ridge known locally as by the “young man afraid of Indians” became angry at the young Ghost dancers, and wired for Custer’s old brigade, the 7th Calvary. The soldiers unleashed unspeakable sexual violence and outright killed upwards of 300 Lakota people, many shot in the back. The United States is a young country indeed if wars were still being fought to expand the country’s territory a mere 126 years ago.

Attending to Hillerman’s ghostly apparitions with a critical, historic perspective, we are encouraged to contend with our own ghosts—real and metaphorical, personal and national. This may lead us away from the dark grip of forgetting, and into remembering the depths of Indigenous struggles. In this way, ghosting might offer not just the thrill of a indulging in a fictional mystery novel, but an avenue opening onto understanding, recognition, and healing.