by Sophie Ell, Senior Digital Hillerman Fellow

Originally published on Celebrating New Mexico Statehood, 8/1/2018

As my last term as a Hillerman graduate fellow is coming to an end, and as I am wrapping up my last project assignment, I have an opportunity to look back and reflect on the many encyclopedic entries I have written, reviewed, and edited over the past two years. Looking back positions us in a specific point in time, with a specific awareness and the benefit of having cumulative knowledge that allows for a critical assessment. The same is true for the overall perspective we, the developing team of the eHillerman portal, apply to our work. Here we are, in the middle of the second decade of the 21st century, working, for example, with the original manuscript of Dance Hall of the Dead, which was published in 1973. On the one hand, we are quite removed from important events that happened 40 or 50 years ago, when Hillerman was writing his novels, and can only speculate and imagine certain experiences (and their meaning at the time) based on the research we do. On the other hand, we have the advantage of a retrospective, analytical point of view.

A term that exemplifies this historical grasp is “Vietnam.” It appears in Dance Hall of the Dead in reference to a minor character, a Zuni Native American, who is using and dealing drugs, mainly heroin. The drug habit, as Hillerman implies, is a direct result of the character’s combat experience in the Vietnam War. In 1973, the war was not even over yet, and Hillerman does not elaborate on its effects on returning troops and on American society as a whole. Defining a term like “Vietnam” 40 year later, we now know that the prolonged and deadly war was one of the most costly of the U.S.’s overseas operations, and one that it had bitterly lost. Several foreign wars later, in the year 2016, homeless veterans stand at major intersections around Albuquerque, as they do in the rest of the country, asking for spare change. Their makeshift cardboard signs often read: VETERAN; ANYTHING HELPS; GOD BLESS. Many of them are young, some of them are old. It is hard to tell which war they fought in. Vietnam? Iraq? Afghanistan?

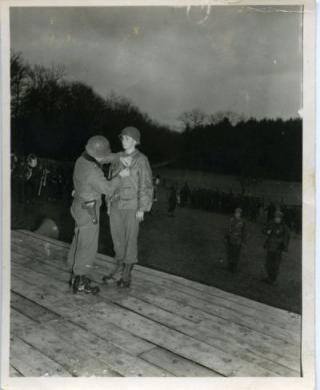

Himself a decorated veteran of World War II, Hillerman was known for having the utmost respect and appreciation for anyone who served in the U.S. armed forces. And yet precisely because of his direct experience, he also understood that exposure to the horrors of war has devastating effects, whether physical, mental, emotional, or spiritual, on most every deployed soldier. Some, returning back to their home country, families, and communities, seek help and healing. Others, as evident in Hillerman’s writing, succumb to insatiable appetites for drugs and alcohol, or worse—money, power, and violence. And while these dark forces serve as intriguing themes of suspense in a good mystery novel, they also point to social ailments that touch individuals of diverse ethnicities and backgrounds, remaining unresolved to this day both on and off Indian reservations, across urban and rural communities alike throughout the nation.

Historical perceptions change, and with them the context, meaning, and significance of events. The way we view Hillerman’s early works now is only relevant for our own particular moment. If, as we hope, the content that we generate today for the portal remains available to the public in the next few decades, how would it be regarded in the future? How might it need to be updated and modified to fit a different perspective? What kind of new lessons would we be able to learn with the passing of time?

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Image: "Tony Hillerman Receiving the Purple Heart, February 9, 1945," photograph, Tony Hillerman Pictorial Collection (000-501-0425-01). Center for Southwest Research, University Libraries, University of New Mexico.